Senescence, a stable and generally irreversible state of cell cycle arrest, is a double-edged sword in cancer biology. Initially thought to be a tumor-suppressive mechanism that prevents potentially malignant cells from continuing to divide, senescent cells are now recognized for their potential to drive tumorigenesis under certain circumstances. Recent updates to the Hallmarks of Cancer framework underscore this dichotomy, making senescent cells—and especially their senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)—an important topic in cancer biology.

This blog looks at the role of senescence in cancer, with a focus on SASP biology, experimental readouts, and how key proteins in associated pathways are being leveraged in emerging senescence-targeted therapies.

< Jump to the product list at the end of this blog >

|

Replicative Senescence vs Cancer-Associated Senescence When senescence was first described in 1961 by Hayflick and Moorhead, it referred to the finite ability of human cells to divide in culture—a phenomenon later termed replicative senescence. Foundational in the study of aging, this discovery demonstrated that normal cells lose their capacity to divide due to the progressive shortening of telomeres—the protective DNA sequences at the ends of chromosomes. |

What are the Hallmarks of Cancer?The Hallmarks of Cancer1-3 are a research framework that organizes the key traits cancer cells acquire in order to grow and spread. Initially described by Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg in 2000, the framework groups the underlying mechanisms of cancer into a series of smaller subsets to advance discovery. The concept was expanded in 2011 to include two additional hallmarks and two enabling characteristics, and again in 2022 with four new emerging hallmarks.

|

When telomeres become too short, cells recognize this as DNA damage and activate a DNA damage response (DDR), leading to a permanent cell cycle arrest. By halting cell division, replicative senescence prevents unchecked cell proliferation and the accumulation of genomic mutations, making it an important protective measure against cancer development.

Paradoxically, despite being an effective cancer defense mechanism, senescence has also been linked to tumor development and malignancy. Senescence in cancer is often stress-induced rather than telomere-driven, arising from oncogene activation, oxidative stress, imbalances in cellular signaling networks, and other environmental factors, most notably therapy-induced DNA damage from chemotherapy or radiation treatments, known as therapy-induced senescence (TIS). Cancer-associated senescent cells can persist in tissues and secrete SASP factors that reshape the tumor microenvironment (TME), sometimes in ways that create a more favorable environment for tumor growth and therapy resistance.

What is the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP)?

The SASP is a complex mixture of factors secreted by senescent cells that enables them to communicate both locally and systemically. Instead of being purely cell-intrinsic, senescence can become a regulator of the microenvironment, influencing neighboring tumor cells, stromal cells, immune cells, and vasculature. By transforming senescence from an isolated cell state into an extrinsic influence on surrounding cells, the SASP drives changes in tissue architecture and immune composition that can be either tumor-suppressive or tumor-promoting, depending on the context.

Key SASP factors include proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α) that propagate inflammation and can stimulate proliferation; chemokines (e.g., CXCL10, MCP-1, and RANTES), which recruit immune cells; matrix-metalloproteinases (MMPs), which remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM); and growth factors (e.g., IGF, VEGF, and EGF), which influence cell growth and/or differentiation by signaling through specific cell surface receptors.

|

|

| Immunohistochemical analysis of paraffin-embedded human endometrioid adenocarcinoma using IL-8 (E5F5Q) Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody #94407. | IHC analysis of paraffin-embedded human cervical carcinoma using MMP-2 (D4M2N) Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody #40994. |

The SASP is highly dynamic: Its composition changes over time and varies by cell type and senescence trigger. This means that senescence may demonstrate varying characteristics depending on whether it’s oncogene‑induced or therapy‑induced, with distinct SASP profiles and different implications for drug response studies.

Key Signaling Axes in Senescence and SASP

Many different signaling pathways control the intensity, timing, and composition of the SASP. Understanding which signaling axis is dominant can help inform the best readouts in experimental models.

|

Senescence Signaling PathwaySenescence signaling integrates tumor suppressor pathways such as p53–p21 with DNA damage and stress responses to enforce durable cell cycle arrest. Get the Senescence Signaling pathway |

|

Cell Cycle & DNA Damage CheckpointsCheckpoints at the G1/S and G2/M transitions sense telomere erosion and replication stress to determine whether a damaged cell repairs itself, undergoes apoptosis, or enters senescence. Get the pathways: |

|

Growth Signaling PathwaysmTOR and related growth signaling pathways influence SASP composition and intensity, and play a role in determining whether senescent cells reinforce immune surveillance or a tumor-promoting inflammatory microenvironment. Get the mTOR Signaling pathway |

|

NF‑κB and Stat Transcriptional HubsNF‑κB and Stat3 are major transcriptional hubs for SASP cytokines and chemokines, integrating upstream signals from DNA damage, pattern‑recognition receptors, and cytokine receptors to promote chronic inflammation. Get the pathways: |

|

p38 MAPK and Stress KinasesStress‑activated kinases such as p38 MAPK respond to DNA damage and oxidative stress signals by activating the NF‑κB‑driven transcription of SASP genes, allowing senescent cells to maintain a pro‑inflammatory SASP. Get the p38 MAPK Signaling pathway. |

How the SASP Shapes the Tumor Microenvironment

In its acute phase—such as during wound healing, development, and early oncogene activation—signaling outputs from the SASP reinforce tumor suppression by strengthening senescence-associated growth arrest and recruiting immune cells that recognize and clear damaged or pre-malignant cells. At this stage, SASP‑driven inflammation primarily supports immune surveillance and tissue homeostasis rather than cancer progression.

However, when senescent cells persist and become chronic, they can reshape the TME in ways that overlap with other Cancer Hallmarks to drive tumor progression. Through SASP signals, senescent cells can promote inflammation, which is normally part of the body’s protective response to support tissue repair after damage. However, in the tumor context, it can instead contribute to persistent immune suppression and tumor survival. SASP factors are also involved in driving invasion and metastatic spread, primarily through enzymes like MMPs, and can stimulate angiogenesis (tissue vasculature) to provide tumors with an increased blood supply. Another important consequence of chronic SASP signaling is the reprogramming of stromal and immune cells, shifting the TME to favor cancer progression and therapy resistance.

This dual role of SASP means that therapeutic strategies aimed at inducing, modulating or removing senescent cells must be carefully timed and tailored to the specific tumor and treatment window—a complex challenge that is still under active investigation.

Biomarkers Identify SASP and Senescent Cells

There is no universal biomarker of senescence, owing to the fact that biomarkers vary based on the type of senescence induction, cell type, and microenvironment. As such, senescence is commonly defined using multiple biomarkers in aggregate.

Common measures for identifying senescent cells include:

- Stable cell cycle arrest: Senescent cells no longer divide, even under growth stimulation, and typically upregulate the cyclin‑dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p16 and p21, which enforce G1 arrest.

- Loss of proliferation markers: The absence of Ki-67 and PCNA helps pinpoint cells not engaging in the cell cycle.

- Persistent DNA damage: Indicators like γH2AX (phospho‑histone H2A.X Ser139) and 53BP1 can mark unresolved damage and chronic DNA damage response.

|

|

| Immunofluorescent (IF) analysis of HeLa cells, untreated (left) or UV-treated (right), using Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139) (20E3) Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody #9718 (green). Actin filaments have been labeled with DyLight 554 Phalloidin #13054 (red). | IF analysis of HCT 116 cells, either wild-type (left) or 53BP1 knockdown (right), using 53BP1 (E7N5D) Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody #88439 (green). Actin filaments were labeled with DyLight 554 Phalloidin #13054 (red). Samples were mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI #8961 (blue). |

- β-galactosidase activity: Detected at pH 6, senescence‑associated β-gal is a classic senescence marker.

- Altered chromatin landscapes: Features such as senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF), DNA decondensation, and global changes in histone marks reflect stable remodeling of the epigenome.

- Nuclear architecture and physical changes: Lamin B1 reduction, chromatin reorganization, and increased lipid droplets further identify senescent cell populations.

IHC analysis of paraffin-embedded normal human breast using Lamin B1 (E6M5T) Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody #17416.

In practice, senescence experiments typically combine several of these markers—such as SA‑β‑gal, proliferation markers, DDR foci, and quantitative measurement of SASP factors (for example, IL-6, IL-8, or MMPs)—together with CDK inhibitors p16 and p21 as early cell cycle arrest readouts to distinguish senescent cells from quiescent or terminally differentiated cells. Designing experiments that leverage multiple orthogonal readouts (e.g., β‑gal + Ki67 loss + γH2A.X + a SASP cytokine panel) can help to build a convincing senescence story for reviewers and collaborators.

Explore additional ways of detecting senescent cells in our blog: 10 Must-have Markers for Senescence Research

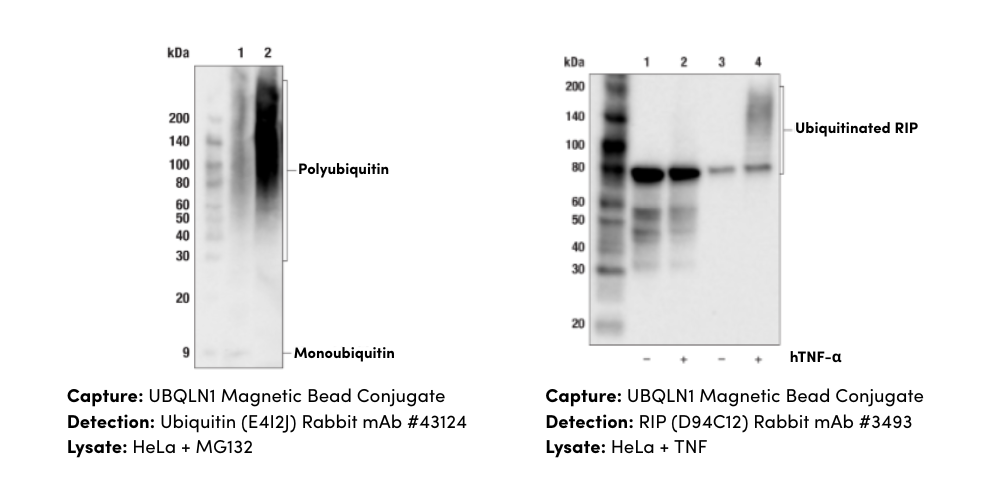

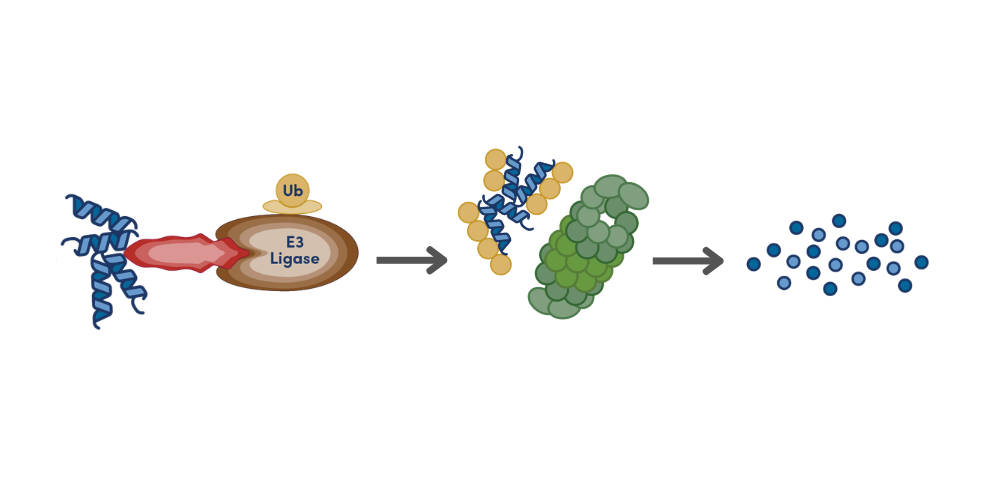

From SASP Pathways to Therapeutic Targets

Increasingly, cancer therapies seek to target senescence through the use of senolytics, which selectively kill senescent cells, and senomorphics (sometimes called senostatics), which modulate the effects of the SASP on surrounding cells and tissue. Although these drugs are primarily at the basic research and preclinical stages of investigation, preliminary data suggest that they may increase the efficacy of established cancer treatments, including chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Combinatorial strategies are also being investigated. These include delivering Quercetin (a plant-derived flavonoid) with Dasatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) to eliminate senescent cells, and combining mTOR, Stat3, and NF-κB inhibitors as a senomorphic treatment.

Senolytics aim to exploit senescent‑cell vulnerabilities in pro‑survival pathways to induce apoptosis, whereas senomorphics suppress detrimental SASP outputs while leaving the senescent arrest intact, which may better preserve beneficial, transient senescence responses. In preclinical models, both strategies can enhance responses to chemotherapy or immunotherapy; however, broad senolysis may disrupt the homeostatic or wound-healing functions of senescent cells, underscoring the need for precise biomarkers and delivery strategies.

Proposed senomorphic treatments include inhibitors of NF‑κB and mTOR signaling (such as rapamycin, metformin, and resveratrol), Jak/Stat and p38/MAPK pathway inhibitors, ATM and HDAC inhibitors, BET (bromodomain and extra‑terminal) inhibitors, glucocorticoid pathway modulators, and polyphenols that modulate one or more of these pathways. Monoclonal antibodies that block specific SASP factors—such as Siltuximab (IL‑6) and Canakinumab (IL‑1β)—are also being explored as ways to dial down SASP‑driven inflammation without fully eliminating senescent cells.

The Cellular Senescence Network (SenNet) Program, established in 2021, is proving to be a powerful tool for cancer research. By providing publicly accessible atlases of senescent cells, using data collected from multiple human and model organism tissues, SenNet allows researchers to map senescent cells and SASP profiles with unprecedented detail across tissues, paving the way for antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy research, and vaccines targeted to senescence-specific markers. Furthermore, ongoing work in cancer biology is focused on understanding why some cancer cells undergo therapy‑induced senescence (TIS) and remain arrested, while others experience “senescence escape” and resume growth, often with a more durable, therapy-resistant phenotype.

Honing SASP’s Double‑Edged Sword

Cellular senescence and the SASP can cut both ways in cancer biology—either suppressing early tumorigenesis, or, if unresolved, helping tumors adapt, persist, and resist therapy. With a deeper understanding of the beneficial and adverse effects of SASP, researchers are further honing this double‑edged sword to develop more effective, durable cancer treatments.

Additional Resources

Read the additional blogs in the Hallmarks of Cancer Series:

- Evading Growth Suppressors

- Nonmutational Epigenetic Reprogramming

- Avoiding Immune Destruction

- Tumor-Promoting Inflammation

- Activating Invasion & Metastasis

- Inducing or Accessing Vasculature (Angiogenesis)

- Genome Instability & Mutation

- Resisting Cell Death

- Deregulating Cellular Metabolism

- Unlocking Phenotypic Plasticity

- Sustaining Proliferative Signaling

References

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57-70. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9

- Hanahan D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(1):31-46. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646-674. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25:585-621. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6