The thought of necrotic cell death might bring to mind images from an old horror movie, but as with most processes in cellular biology, it is more fascinatingly complex upon closer investigation.

Necrosis

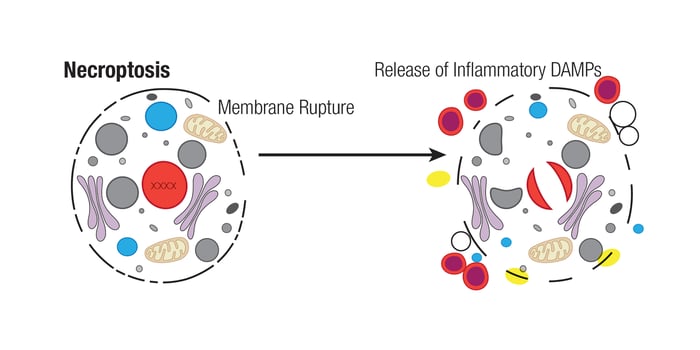

Necrosis has been classically defined as an unprogrammed form of cell death that occurs in response to overwhelming chemical or physical insult. External forces that may lead to this accidental cell death include extreme physical temperature, pressure, chemical stress, or osmotic shock. Rupture of the cell, which is characteristic of necrosis, leads to leakage of the cellular contents into the extracellular space. This causes the release of biomolecules, called Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), that can be recognized by immune cells and trigger an inflammatory response.

While it was previously thought that necrosis was passive and unprogrammed, research has uncovered caspase-independent processes that resemble necrosis. A form of programmed necrosis, termed necroptosis, can occur due to extracellular signals (death receptor-ligand binding) or intracellular cues (foreign microbial nucleic acids) and is actively inhibited by caspase activity.

There are many other types of programmed necrotic cell death processes as well, such as pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and NETosis, that I will describe in upcoming blogs. Forms of necrotic cell death, particularly the programmed processes, are important as they have been implicated in the pathology of many diseases, including inflammatory autoimmune diseases, fibrosis, and neurodegeneration-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

Necroptosis

Necroptosis, which is a regulated form of necrosis, is the process of cellular self-destruction that is activated when apoptosis is otherwise prevented. Necroptosis is distinct from apoptosis and other forms of programmed necrotic cell death in that it progresses independently of caspase activity. Instead, it requires the RIPK3-dependent phosphorylation of MLKL. This phosphorylation event allows MLKL to generate a pore complex in the plasma membrane leading to the secretion of DAMPs, cell swelling, and membrane rupture. One can observe different stages of cell breakdown during necroptosis, including the swelling of organelles, breakage of the cell membrane, and eventually, the disintegration of the cytoplasm and nucleus.

Necroptosis is highly immunogenic in nature and is useful as a host defense mechanism against viruses and other pathogens. It has been shown to occur when viral machinery inhibits caspase activity, thus allowing the cell to self-destruct to limit viral replication. Necroptosis has also been detected in other pathological conditions, including ischemic brain injury, myocardial infarction, and cell death associated with chemotherapy. It is also activated in inflammatory diseases, neurodegeneration, and cancer.

Necroptosis is often triggered by extracellular stimulation when ligands, such as TNF-α, bind to Death Receptors (DRs) in the cell membrane. Receptors in this TNF superfamily include TNFR1, Fas/CD95, DR4/TRAIL-R1, and DR5/TRAIL-R2. Once activated, these receptors bind to the adaptor proteins, TRADD and TRAF2, leading to the downstream activation of RIP kinases.

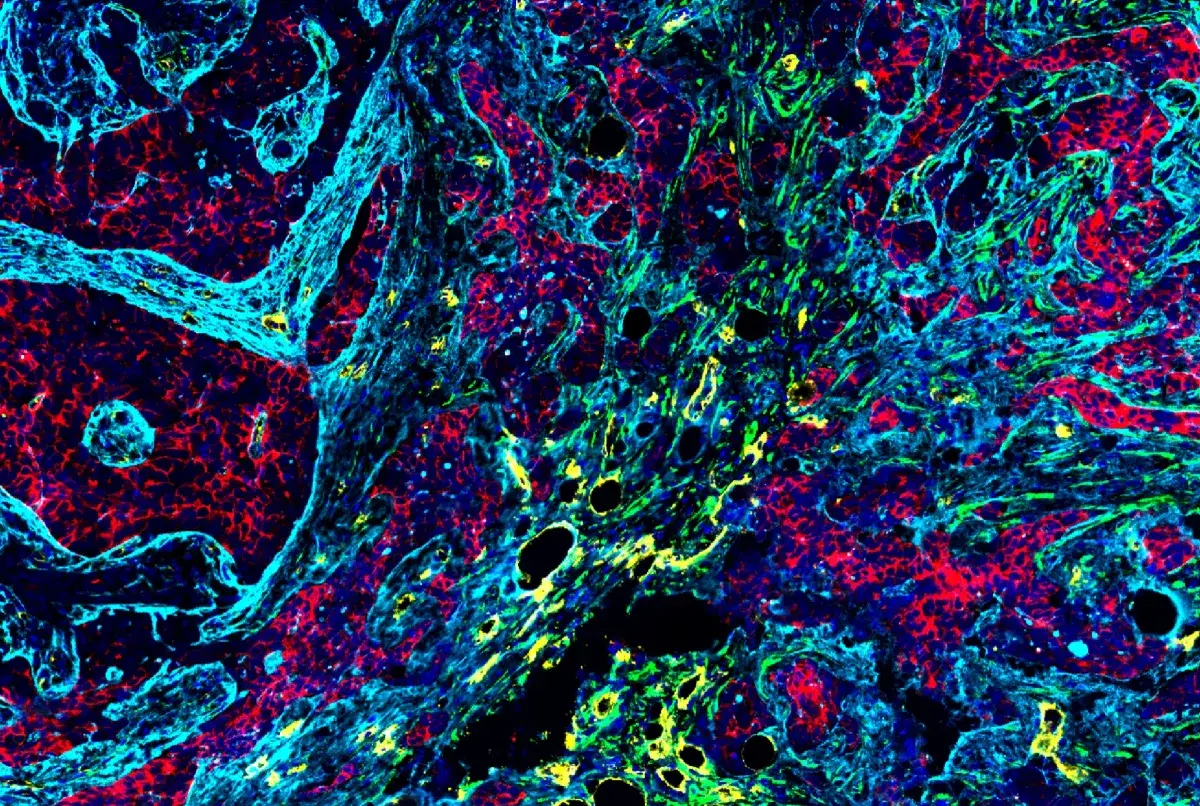

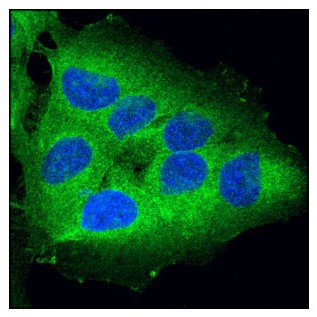

RIP kinases are Ser/Thr kinases that regulate inflammation and cell death. The above image shows a Confocal IF analysis of OVCAR8 cells using RIP (D94C12) XP® Rabbit mAb #3493 (green).

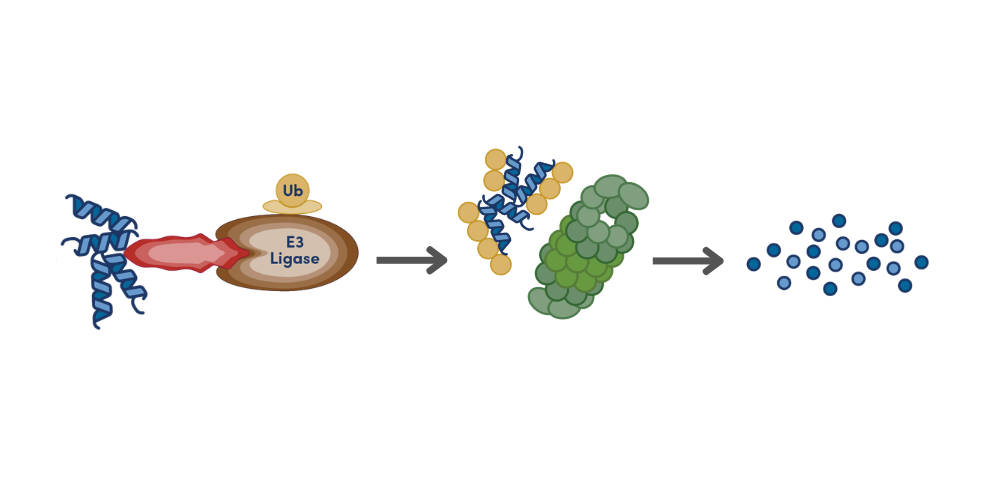

Canonically, RIPK3 is activated via phosphorylation at Ser227 (Thr231/Ser232 in mouse) after forming a complex with RIPK1, which itself is also autophosphorylated at Ser166, Ser161, and Ser14/15. This complex, called the necrosome, then phosphorylates MLKL at Ser358 (Ser345 in mouse). Activated MLKL is then able to oligomerize and form pore complexes that translocate to the plasma membrane. There, these pore complexes interact with phosphatidylinositides and induce membrane permeabilization and the destruction of the cell. MLKL-induced permeabilization of the plasma membrane leads to influx of Ca2+ or Na+ ions and direct pore formation with the release of DAMPs, including mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), HMGB1, interleukin (IL)-33, IL-1α, and ATP. The presence of inflammatory DAMPs in the extracellular space serves as a signal to recruit immune cells to the damaged or infected tissue.

Phosphorylation of MLKL leads to pore formation and is a marker for necroptotic cells. The above image shows a confocal IF analysis of L-929 cells pre-treated with Z-VAD (20 μM, 30 min) followed by treatment with SM-164 (100 nM) and Mouse Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (mTNF-α) #5178 (20 ng/mL, 2.5 hr) using Phospho-MLKL (Ser345) (D6E3G) Rabbit mAb #37333 (green).

Phosphorylation of MLKL leads to pore formation and is a marker for necroptotic cells. The above image shows a confocal IF analysis of L-929 cells pre-treated with Z-VAD (20 μM, 30 min) followed by treatment with SM-164 (100 nM) and Mouse Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (mTNF-α) #5178 (20 ng/mL, 2.5 hr) using Phospho-MLKL (Ser345) (D6E3G) Rabbit mAb #37333 (green).

It is important to note that RIPK1 is highly regulated and also plays a role in complexes that initiate NF-κB signaling and survival, apoptosis, or, alternatively, necroptosis. Thus, analyzing the phosphorylation states of the key proteins RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL is an important step in identifying necroptosis.

Alternate triggers of the necroptosis pathway include pathogen activation of Pathogen recognition receptors (PRR), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which activate the adaptors TRIF and ZBP-1 that subsequently interact with and activate RIPK3 independently of RIPK1.

The process of necroptosis can be inhibited in various ways. Because it is often dependent upon the activity of RIPK3 and the necrosome, caspase-8 can inhibit necroptosis through cleavage of RIPK1 and RIPK3. In this way, activation of the apoptotic pathway also inhibits necroptosis. Conversely, if the protein FLIP, which is a catalytically inactive homolog of caspase-8, replaces caspase-8 in the apoptotic complex, it can prevent the cleavage of RIPK1 and drive necroptosis instead. Importantly, inhibition of necroptosis has been observed in the presence of necrostatin-1 (Nec-1), a small molecule that has been reported to prevent RIPK1 activity.

Current research suggests that necroptosis plays a major role in cancer as well as several neurodegenerative diseases. It is thought that necroptosis is involved in metastasis; therefore, inhibition of the necroptotic pathway could limit tumor growth. In addition, it has been reported that treatment with Necrostatin-1 improved cell viability in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Taken together, investigation of the mechanisms of necroptosis and other cell death pathways may provide therapeutic insights for the development of novel treatments for a variety of diseases.

Additional Resources

To learn more about the mechanisms, morphology, and key proteins involved in many types of cell death, download the guide below:

Read the additional blog posts in the Mechanisms of Cell Death series:

- Mechanisms of Cell Death: Apoptosis

- Mechanisms of Cell Death: Ferroptosis

- Mechanisms of Cell Death: Pyroptosis

Learn more about CST® TUNEL kits that robustly detect cells undergoing apoptosis and other forms of programmed cell death.

Select References

-

Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(3):486-541. doi:10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4

- Frank D, Vince JE. Pyroptosis versus necroptosis: similarities, differences, and crosstalk. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26(1):99-114. doi:10.1038/s41418-018-0212-61.

- Escobar ML, Echeverría OM, Vázquez-Nin GH. Necrosis as Programmed Cell Death. In: Cell Death - Autophagy, Apoptosis and Necrosis. InTech.